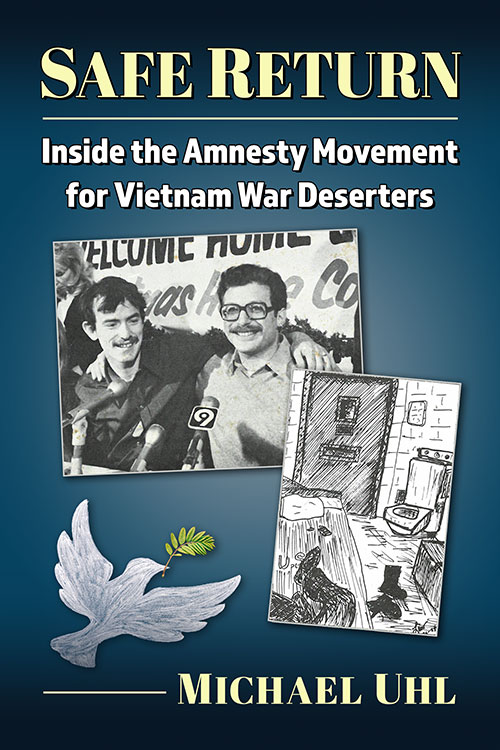

Michael Uhl’s Safe Return: Inside the Amnesty Movement for Vietnam War Deserters (McFarland, 271 pp. $29.95, paper; $17.99, Kindle), a literate part memoir, part history, part polemic, is the no-holds-barred story of a dynamic two-person organization that advocated universal unconditional amnesty for Vietnam War draft dodgers, draft resisters, deserters, and those with bad paper discharges.

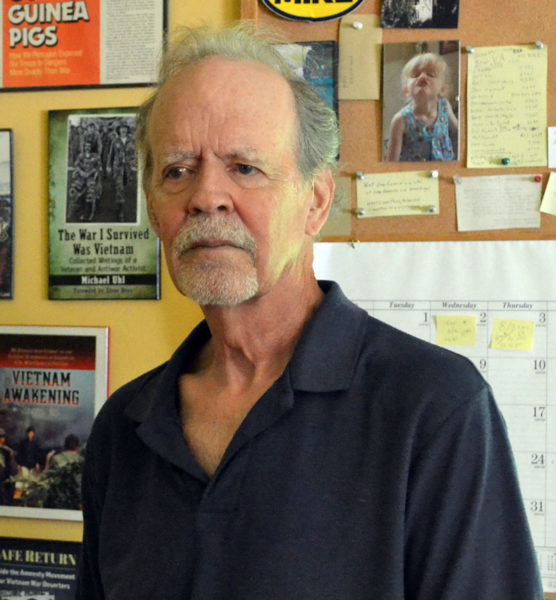

Uhl served as a U.S. Army Lieutenant in Vietnam in 1968-69, where he led a combat intelligence team with the 11th Infantry Brigade. He wrote about his war experiences and political radicalization in the 2007 book, Vietnam Awakening: My Journey from Combat to Citizens’ Committee of Inquiry on U.S. War Crimes in Vietnam.

The new book covers Uhl and Tod Ensign’s efforts from 1971-75 to create the Safe Return Amnesty Committee and its offshoot, Families of Deserters for Amnesty. Uhl chronicles and analyzes the groups’ tactics, strategies, successes, and failures. The failures include an inability to work with some individuals and other organizations with analogous goals but different agendas.

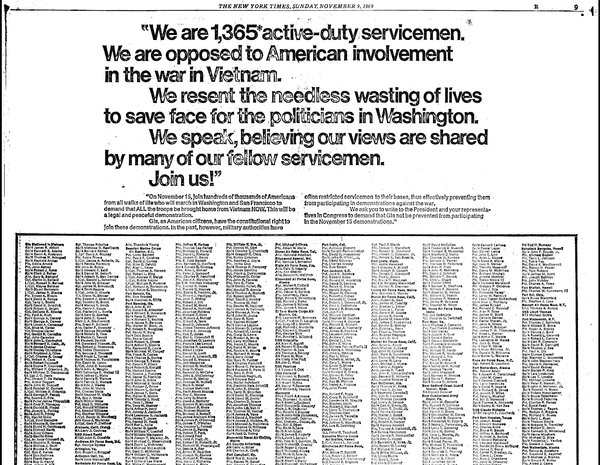

In pre-social media times, Safe Return generated an enormous amount of paper – newsletters, correspondence, flyers, advertisements, and staged public surrenders of several deserters (“semi-retired veterans”) and draft evaders, to publicize its message. This led in part to books, newspaper and magazine articles, congressional hearings, support by politicians and celebrities, and even two movies.

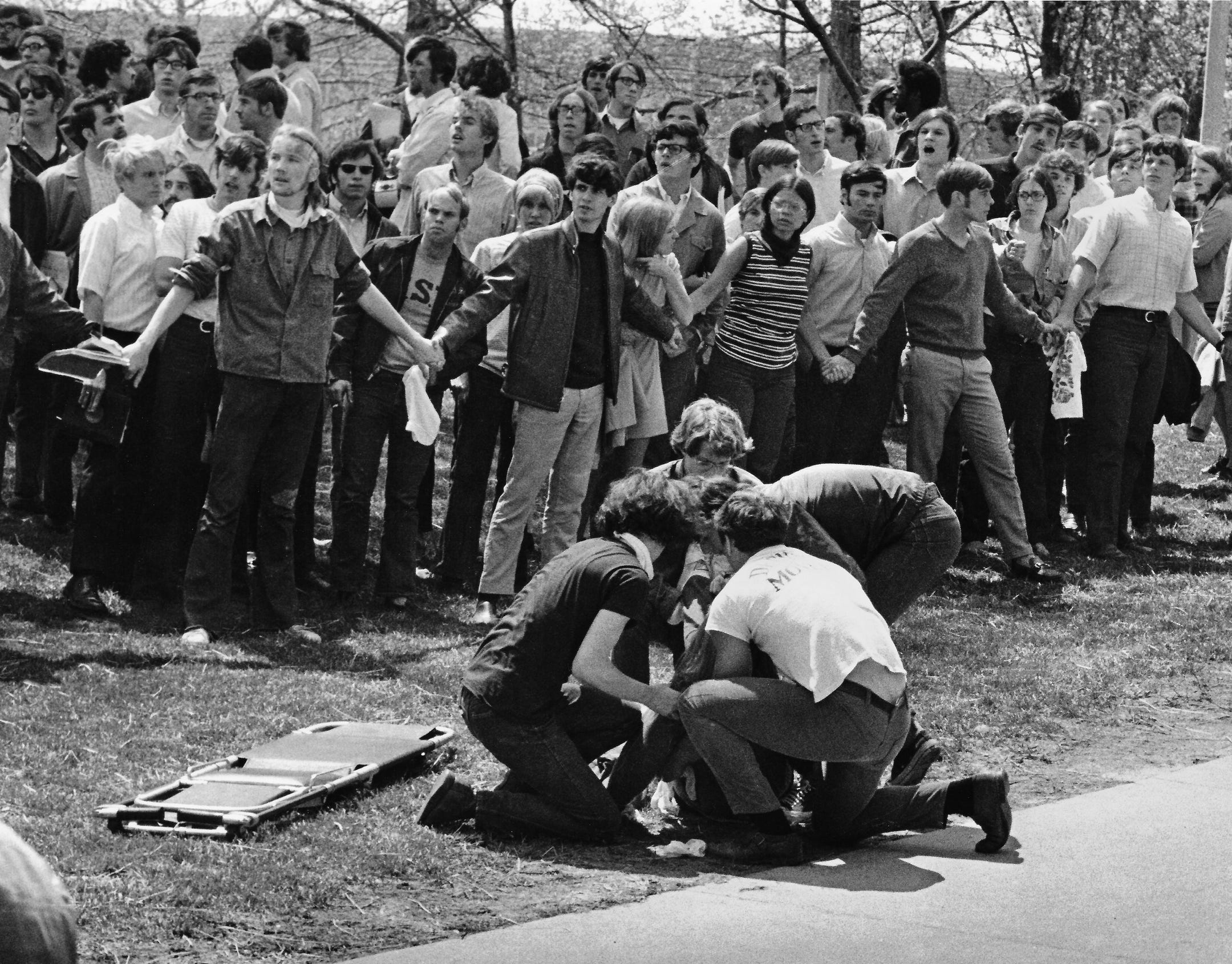

Uhl had hoped to translate the antiwar sentiment into universal amnesty for all and was always consistent in that uncompromising position. However, the elimination of the draft, he posits, extricated “the principal stone from the heels of draft-age youth, no longer requiring their service in the armed forces…, [such that] the grit of popular resistance was removed from the machinery of war.”

In 1974, President Ford created the Clemency Board. In January 1977, President Carter issued pardons for men who evaded the draft Vietnam War draft by leaving the country and those who did not register their local draft boards, but not for deserters. Carter later created a Special Discharge Upgrade Program, which could affect about half of all bad paper discharges. Who is to say that Uhl’s “cigar-box enterprise” did not have an immeasurable effect on all these events?

Marc Leepson, The VVA Veteran’s Arts Editor, asked me if I would be willing to review this book. I had no problem agreeing to do so. All books should be reviewed, particularly by those who might disagree with some of the book’s major premises.

A further question is whether my fellow Vietnam War veterans should read the book because they showed up then and did their duty. Of course, they should.

This well-written book is worth a read because you will learn about a particular part of the antiwar movement. However, it has been more than 60 years since politicians committed America to this unnecessary war, and then different politicians abandoned our South Vietnamese allies to their dismal fate.

These politicians are the ones against whom you may continue to hold a grudge, so that such horrendous mistakes might not happen again. On the other hand, after all this time, it may be healthier for you to be at peace with antiwar activists, draft dodgers (a couple of whom have been elected president), draft resisters, and “semi-retired veterans.”

–Harvey Weiner

Ronnie Foster sums up his opinion of the Vietnam War with words he attributes to his protagonist in his novel, Last Train Runnin (R.D. Foster, 415 pp.; $21.25, paper):

Ronnie Foster sums up his opinion of the Vietnam War with words he attributes to his protagonist in his novel, Last Train Runnin (R.D. Foster, 415 pp.; $21.25, paper):