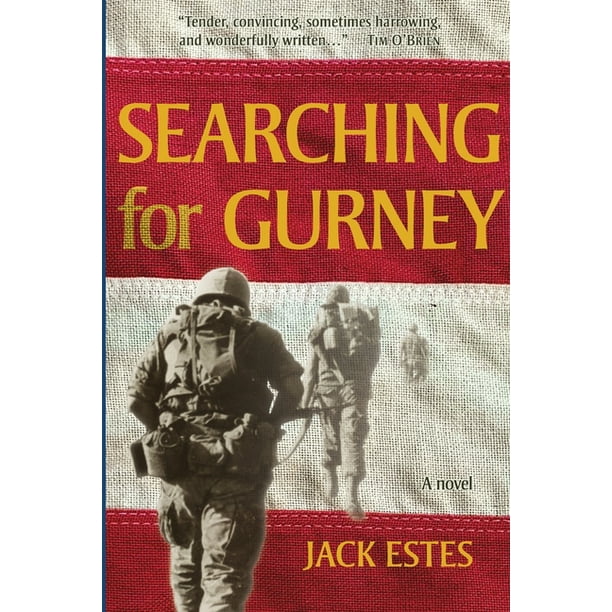

Jack Estes’ Searching for Gurney (O’Callahan Press, 328 pp. $17, paper; $9.99, Kindle) is a welcome return to high-quality Vietnam War literary fiction. Estes served as a rifleman with the 9th Marines and later with a CAP unit during his 1968-69 Vietnam War tour of duty. He’s written two other books that deal with the war: A Field of Innocence (2014), a memoir, and a A Soldier’s Son (2016), a novel.

With Searching for Gurney’s first sentence—“JT woke, but they were still dead,”—the reader is immediately enmeshed in the world of a Vietnam War veteran’s post-traumatic stress. The veteran, JT, believes he should be able to handle his new civilian job because, Estes writes, “he’d led men into battle, run patrols, set ambushes, called in gunships, destroyed villages and hillsides. He’d fired rifles, machine guns, tossed grenades, and killed enemy soldiers so often that not killing felt odd. So this mailroom job was a skate.”

JT’s wife says he’s been different since he returned home from war. He never smiles and seems to carry a sense of danger with him. She “thought violence was when he punched a hole in the wall or broke a doorjamb,” Estes says. “That wasn’t violence.”

For his part, JT believes that no matter how much he and his wife fuss, God meant them to be together. “Why else would he have survived Vietnam?” Though he is too young to legally buy beer, he often goes to bars and drinks. After getting into fights, he thinks maybe “he’d be better off back in Nam.”

Coop served alongside JT. He’s back home just long enough to attend his grandfather’s funeral before he has to return to the war. While contemplating the funeral service, he thinks, “This wasn’t death. Death was that first patrol. This was sleep.” He also drinks in the morning so he won’t “stick a gun in his mouth.” And he’s glad to be going back because he “wanted war and didn’t care if he died. It was only when he felt at risk that he felt alive.”

Hawkeye completes the trio. He winds up in the Marines to avoid a jail sentence and quickly discovers in Vietnam that the “one thing you can always count on is that you can’t count on anything.” A fourth important character, Nguyen Vuong, joins the three Americans in the book’s third act.

The Vietnamese who are engaged in war with the Americans, Estes writes, believe they are fighting “in a great and noble cause that will be remembered until the end of time.” They read Shakespeare and share their poetry with each other.

The Americans pop amphetamines to stay alert, carry sawed-off shotguns, and live by the philosophy, “They say go. We go.”

They find peacefulness when they can “listen to the silence,” and are confused by the strangeness of hearing rumors of peace talks in the midst of fierce fighting.

In this extremely well-written, time-tangled story, the boyish-looking Lt. Gurney doesn’t make his appearance until the last few pages. He then quickly disappears. That triggers the search in the book’s title, and the plot wraps around itself in an intriguing and satisfying way.

Searching for Gurney doesn’t read like a comic book as so many war novels seem to. It conveys the impact of war through the lens of literary fiction. It’s also one of the few books I reread immediately after I finished it.

Estes’ website is jackestes.com

–Bill McCloud