Set the Night on Fire: L.A. in the Sixties (Verso, 800 pp. $34.95) is a history of the social and political struggles of the 1960s unlike most others. For one thing, Jane Fonda is mentioned only six times in 640 pages of text. What authors Mike Davis and Jon Wiener do, instead, is probe and dissect diverse communities in Los Angeles deeply below the surface of the usual panorama.

A special ideological perspective or historical interest is needed to read it. Even its vocabulary is different. Davis, an author and MacArthur Fellowship recipient, and Wiener, a history professor and longtime contributing editor to The Nation magazine, for example, write about “uprisings” against “grinding forces of oppression.”

Black revolts against racism and inequity are at the book’s core, but the authors also cover “reciprocal influences and interactions.” Formal and informal alliances include the Vietnam War antiwar movement. There are competing or conflicting cultural outlooks, strategies, tactics, and agendas.

In 1965, Los Angeles’ police chief compared a Black uprising in Watts, one of the poorest sections of the city with 8,000 people and 20 percent unemployment, to the fighting in Vietnam. Thirty-four people died. More than 1,000 suffered major injuries. A National Guard report claimed that the Viet Cong were involved. (In fact, the “bungled” police arrest of a drunk driver on a hot summer’s night sparked the violence.)

In June 1967, President Lyndon Johnson arrived in L.A. for a $1,000-a-plate Democratic Party fundraising dinner at the Century City Plaza Hotel. A thousand police officers faced off outside against 10,000 protesters. Ensuing violence caused the Secret Service to prepare—if necessary–to evacuate the president by helicopter from the roof of the hotel. The organizers had a legal march permit, but some sat down and halted it in a show of civil disobedience.

Antiwar protesters in front of the Century City Plaza Hotel

Century City was a turning point. White middle class participation in the protest convinced Johnson he was unlikely to win the 1968 presidential election. In March he announced he would not run after Sen. Eugene McCarthy’s strong showing in the Democratic primary in New Hampshire was followed by Sen. Robert Kennedy’s entry into the race.

McCarthy and Kennedy had similar plans to end the war, premised on negotiations, but the Left wanted an immediate American military withdrawal. By 1967, its leaders already had launched a third-party strategy, organizing the Peace and Freedom Party.

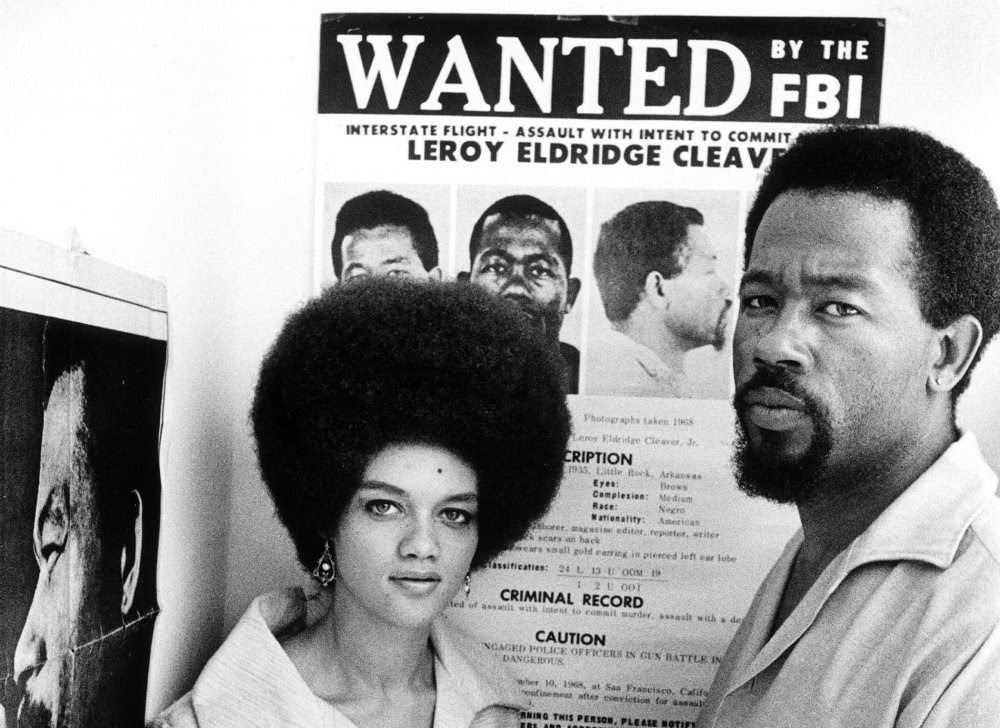

Their desired presidential candidate was Martin Luther King, Jr., who declined the honor. The Black Panthers and White radicals then went after comedian and Civil Rights activist Dick Gregory. Black nationalists wanted Eldridge Cleaver, a former convict and author who called for “a second front” on the West Coast to support the Viet Cong.

Cleaver was two years short of the U.S. Constitution’s minimum age requirement to run for president, but in August 1967, the PFP state convention in L.A. voted 161-54 to endorse him. On Labor Day the national convention nominated him.

In April 1968 Cleaver was involved in a shoot out with Oakland police, and charged with attempted murder. Protests by leading liberal writers and intellectuals led to his release on bail. Cleaver then “lost interest.” On Election Day, he endorsed a pig whom protesters at the Democratic National Cconvention in August had nominated as their candidate. Three weeks later he fled to Algeria.

Bitterly critical of Eldridge and the PFP division, Set the Night on Fire nonetheless heralds the registration drive to get the party on the ballot in California as “a triumph of historic proportions.” The PFP become the first left-wing party to win official recognition in 20 years. The authors credit it as “the first evidence anywhere in the country of LBJ’s vulnerability to an electoral challenge.”

The book has eight sections and 36 chapters. Overlapping events make the chronology difficult to follow. Mexican Americans and Chicano Moratorium demonstrations are covered in the seventh section. Asian Americans and “other liberations” in the last. One of the most interesting chapters deals with draft resistance and the sanctuary movement.

Occasionally, police, prosecutors, or judges sympathized with draft resisters and deserters. One soldier from Fort Ord asked his girlfriend to marry him while taking refuge in a Quaker meeting house. Their wedding took place during a recess in his later court-martial for desertion. The Army prosecutor spoke at the ceremony. He wished the bride and groom happiness, and said he had “nothing personal” against him. The deserter received a dishonorable discharge, but no prison time.

Set the Night on Fire is a valuable doorstop reference book, but will never reach a popular audience. Which is perhaps unfortunate. Insights and lessons are buried in its many pages. Some would be useful to recall as resurgent waves of Black and White protest today seek to overcome fault lines in the American Dream.

–Bob Carolla