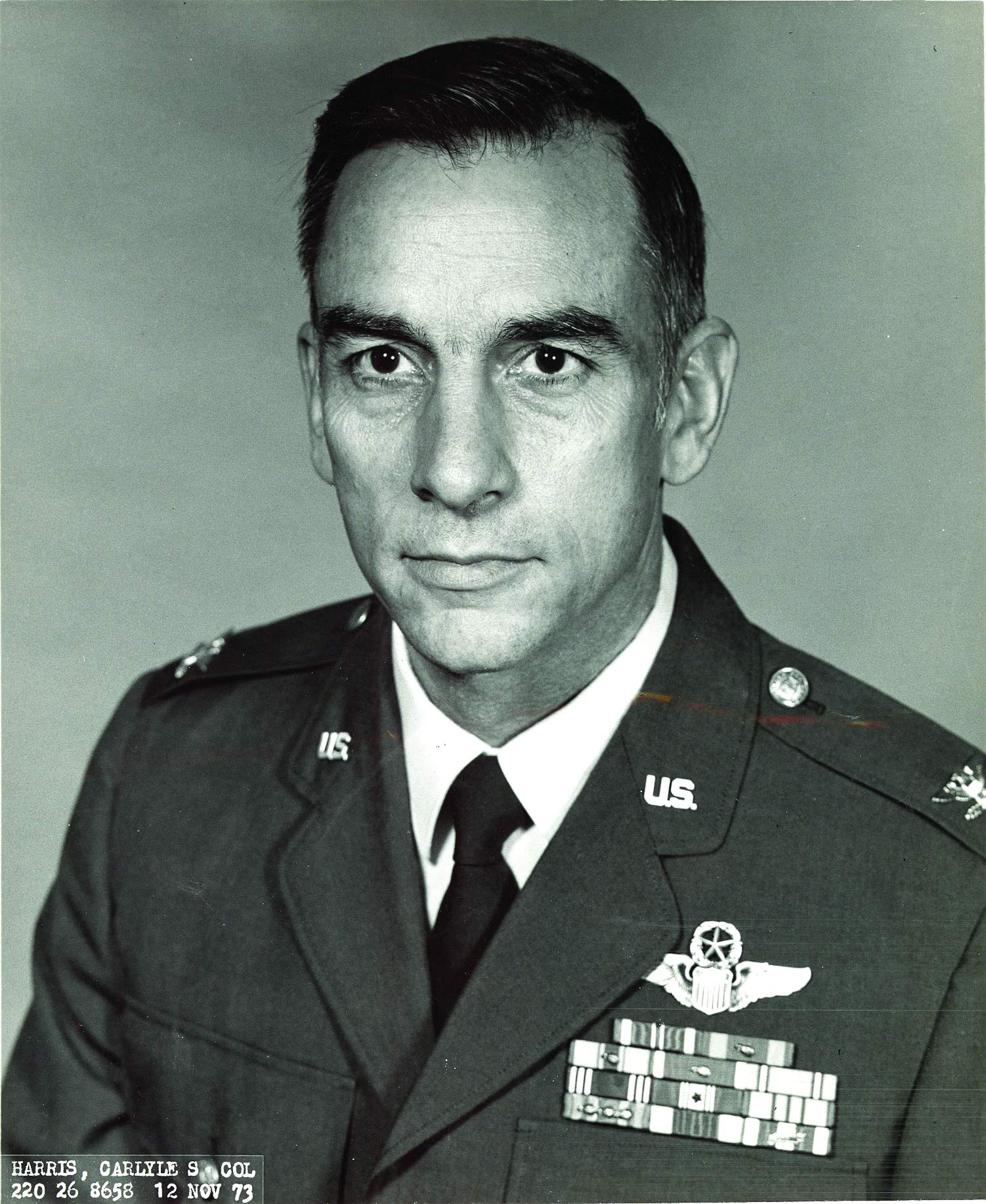

More than a few American aviators have written about their time as prisoners in Hanoi during the Vietnam War. Tap Code: The Epic Survival Tale of a Vietnam POW and the Secret Code that Changed Everything (Zondervan, 256 pp. $26.99, hardcover; $14.99, Kindle); $26.99, audio CD), a memoir by retired Air Force Col. Carlyle “Smitty” Harris, a POW for nearly eight years, differs because it intersperses chapters of his wife Louise’s experiences during his time in captivity. The two of them exemplify the highest form of dedication to the nation from an American military family.

Sara W. Berry, an author and publisher, helped Smitty and Louise Harris finish the book, which he had started writing in the late 1970s.

In the Vietnam War, Smitty flew the F-105, and on April 4, 1965, became the sixth American shot down over North Vietnam. He is best known for recalling a Second World War tap code that a sergeant taught him during an after-class chat at survival school. After he was captured, Smitty taught the code to fellow POWs who passed it on to others.

The code provided a communication system in an environment in which guards enforced silence and prisoners spent long periods in solitary confinement. In his memoir, A P.O.W. Story: 2801 Days in Hanoi, Col. Larry Guarino says that the code was “the most valuable life- and mind-saving piece of information contributed by any prisoner for all the years we were there.”

Smitty Harris’ account of his imprisonment parallels what other POWs have recorded over the past forty-five years. All of them, including Harris, endured brainwashing, torture, starvation, untreated illnesses, and isolation at multiple prison camps in the Hanoi area, including the infamous Hanoi Hilton. He recalls the names and behavior of fellow POWs, focusing on their ability to comply with the Code of Conduct. He emphasizes the importance of a religious belief in maintaining a positive mentality. “GBU”—God bless you—was the most frequent message tapped out in prison, he says.

Louise Harris also coped with challenges she never expected. She and the couple’s two daughters had accompanied her husband to Kadena Air Base, Okinawa. When the United States began to bomb North Vietnam, his F-105 squadron deployed to Korat Air Base, Thailand. Five weeks after Smitty Harris was shot down, Louise gave birth to their only son.

As “the first MIA spouse to return to the States,” Louise Harris encountered military regulations that were unfair to her and the children. Consequently, she faced down the Secretary of the Air Force and leaders of the VA, thereby helping clear the path for wives of those Americans who would be subsequently taken captive.

She solved another major problem by phoning the president of the General Motors in Detroit—collect. After settling in Tupelo, Mississippi, Louise Harris went on to play a role in planning procedures related to the POWs’ release.

Smitty Harris gained his freedom in 1973. He and his wife smoothly blended back together, raised their children, and happily settled in Tupelo following his Air Force retirement. He explains how readjusting to life back home was not as easy for other POWs and their wives.

Americans who spent time in Hanoi prisons shared a deep friendship and enjoy frequent reunions. They recognize themselves as a breed apart.

—Henry Zeybel