Reading and reviewing books about the Vietnam War in recent years has taken me down an intellectual path that grows ever more difficult. In Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the Memory of War, Viet Thanh Nguyen says that wars “are fought twice, first on the battlefield and second in memory.” His words constitute an absolute truth when applied to the Vietnam War. Which leads to the vital question: Did America win or lose that war?

In Aid Under Fire: Nation Building and the Vietnam War, Jessica Elkind looks at the war in 1965 and concludes that the American effort was doomed from the start. Fundamentally, nation-building failed to make South Vietnam independent, she says, because the Vietnamese did not support American geopolitical goals set by applying western practices that overlooked the reluctance of recently decolonized Asians to accept them. Consequently, the South Vietnamese rural population did not devote its collective hearts and minds to supporting the anti-communist cause.

Opinions similar to Elkind’s had not precluded President Richard Nixon—and his National Security Adviser and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger—from employing an endgame strategy that “stressed the idea that the war in Vietnam had actually successfully ended.”

On the other hand, in The War after the War: The Struggle for Credibility during America’s Exit from Vietnam Johannes Kadura argues that Nixon and Kissinger foisted the blame for the loss of South Vietnam to the communists on Congress due to the nation’s lack of post-1973 support when Congress reduced military and economic aid.

Meticulously researched, these heavily foot-noted books are masterpieces of scholarship.

Kevin M. Boylan further pursues the question in Losing Binh Dinh: The Failure of Pacification and Vietnamization, 1969-1971 (University Press of Kansas, 376 pp., $34.95, hardcover: $19.99, Kindle). In this book Boylan seeks to come to a determination about whether the war ended in victory or defeat.

Boylan is a history professor at the University of Wisconsin, Oshkosh. From 1995-2005, he worked in the Pentagon as DoD analyst for the U.S. Army staff. His book contains forty-three pages of notes, mainly from archives and interviews.

Pitting the orthodox (people who claim the war was unnecessary, unjust, and unwinnable) against the revisionist, Boylan questions whether “a victory to be lost” existed prior to America’s 1973 exit from Vietnam. In other words, did pacification and Vietnamization work? Following in the footsteps of the Vietnam Special Studies Group, Boylan focuses his study on heavily populated and strategically located Binh Dinh province.

He examines the province’s military, political, economic, and psychosocial aspects by comparing achievements with expectations in Operation Washington Green, a 1969 American pacification plan for the hamlets of Binh Dinh’s four districts. He gives equal attention to North and South Vietnamese and American perspectives.

Using MACV Advisory Team Activity Reports, Boylan shows how South Vietnamese dependency on American leadership continually increased throughout Operation Washington Green and how consequently the Vietnamese failed to attain self-sufficiency. His detailed accounts describe the inherent turmoil that exists when foreign troops babysit a distinctly different society, especially one threatened by insurgents.

Boylan notes that in the Vietnam War there “was, in fact, no such thing as a truly representative province,” but the problems that affected Binh Dinh occurred “throughout a dozen provinces embracing nearly half of South Vietnam’s territory.” When “studied from the bottom up,” it’s plain to see that after the Americans withdrew from the region in 1972, “‘fence sitting’ villagers threw in with the seemingly triumphant Communists,” he says.

If one accepts the failure of Operation Washington Green as a fact, Boylan’s “Conclusion: Triumph Mistaken” stands as a final verdict about the war’s outcome. The “lost victory” hypothesis (that the war was won by 1972 and that Congress “lost” the victory by cutting funds to South Vietnam) is wrong, he says. His conclusion is worth the price of the book.

Boylan points out that the current situations in Iraq and Afghanistan bear disturbing similarities to the Vietnam War. Again, the United States is propping up regimes with disputed legitimacy and military forces with questionable combat motivation.

Our extensive training, material, and logistical assistance in Iraq duplicates our commitment to Operation Washington Green in the Vietnam War, he says.

Gen. David Petraeus’s resurrection of “population-centric COIN” theory allowed Americans to withdraw from Iraq in 2011, but in 2014 Islamic invaders from Syria overran one-third of the country because Iraqi security forces “displayed a shocking lack of will to fight,” Boylan says.

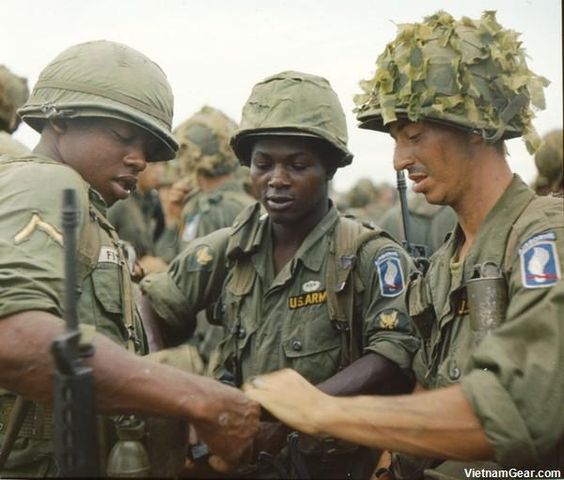

Troops of the 173rd Airborne Brigade, which took part in Operation Washington Green in northern Binh Dinh in 1969

I must add my experience of teaching COIN theory at Air University in the 1960s. We low-ranking instructors laughed inwardly at the naivete of a military plan that called for winning hearts and minds with love. We preferred more direct action, as in: “Grab them by the balls and their hearts and minds will follow.”

Infantrymen who served in Vietnam have told me that, for them, the war ended when pacification and Vietnamization began. They recognized the futility of the task as Boylan describes it: “The government of South Vietnam could spend years—even decades, if necessary—carrying out the nation-building programs required to resolve the underlying grievances that had fueled the insurgency in the first place.”

Furthermore, troops assigned to the task had no training to accomplish it, Boylan says.

I long for the simplicity of the Cold War.

—Henry Zeybel