Dan Dana’s Diary of a Young Man: 1968-1969: Coming of Age at a Cultural Crossroads (Five Palms Press, 110 pp. $0.99, Kindle) is unlike any wartime journal I’ve ever read. And that’s a good thing.

Unlike any other, that is, because the book’s diary entries that cover his last two months in Vietnam and his worldwide travels afterward are based solely on the unedited words he wrote virtually every day more than 50 years ago. Words, by the way, that were not intended for any eyes other than his own.

Dana’s book begins in September 1968 in Qui Nhon, South Vietnam, as the young G.I. is dreaming of what it will be like after gets out of the Army. He has a frequent “urge to write” and a desire to fill up a variety of journals that he refers to as “books” once he’s completed them. He wants to write about things he considers to be “record-worthy.”

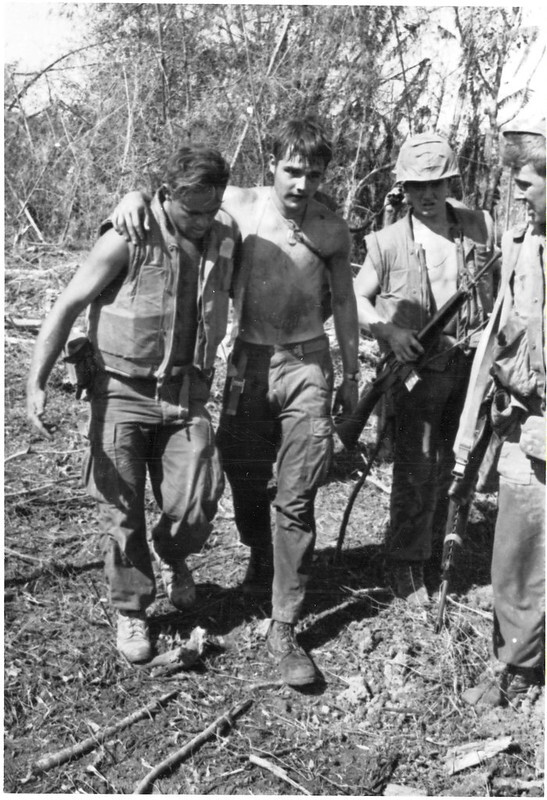

Interestingly, the book’s Foreword is written by VVA Veteran Arts Editor Marc Leepson, who served with Dan in the 527th Personnel Service Company on the outskirts of Qui Nhon in 1968. There’s even a grainy, black-and-white photo of the two of them in the book.

Dana writes that “several GIs” didn’t like the Vietnamese people because “they are not adopting American traits fast enough.” And: “Saigon is beautiful, so many trees. Nearly all of the streets around downtown are canopied with huge shade trees.” As for Vietnamese women, they “seemed to me physically beautiful,” he writes.

The diary covers Dana’s last few weeks of military service. He writes that he planned to make daily entries, and decided that on days when nothing much happened, he’d just say: “Nothing really worthy of petrification today.” Dana considers returning to school or maybe becoming a writer after his discharge.

“This book,” he writes, “is probably the most permanent thing I carry,” which is why he jots down all sorts of notes in it. At age 23, he hopes to get some traveling under his belt after ETSing in Vietnam before returning home.

He goes on R&R to the Philippines and notes that the shorter he gets, the less he feels like writing. After coming back to the 527th, Dana begins smoking marijuana day and night, skips a reveille formation, and is punished by filling sandbags.

When he gets down to single digits, Dana, a life member of Vietnam Veterans of America, notes that he is already is experiencing feelings of nostalgia. Once he’s out, he’s determined to have some adventures before returning to school. We follow his time in Mexico sleeping on the beach, trying to grow a beard, and hanging out with hippies with all that entailed.

Dana adds more countercultural experiences, and ends the book with a series of haiku, such as:

war can be good, eh?

only lessons learned, too late

in history books

Dan Dana’s Diary is one-of-a-kind book, indeed.

His website is https://dandana.us/

–Bill McCloud