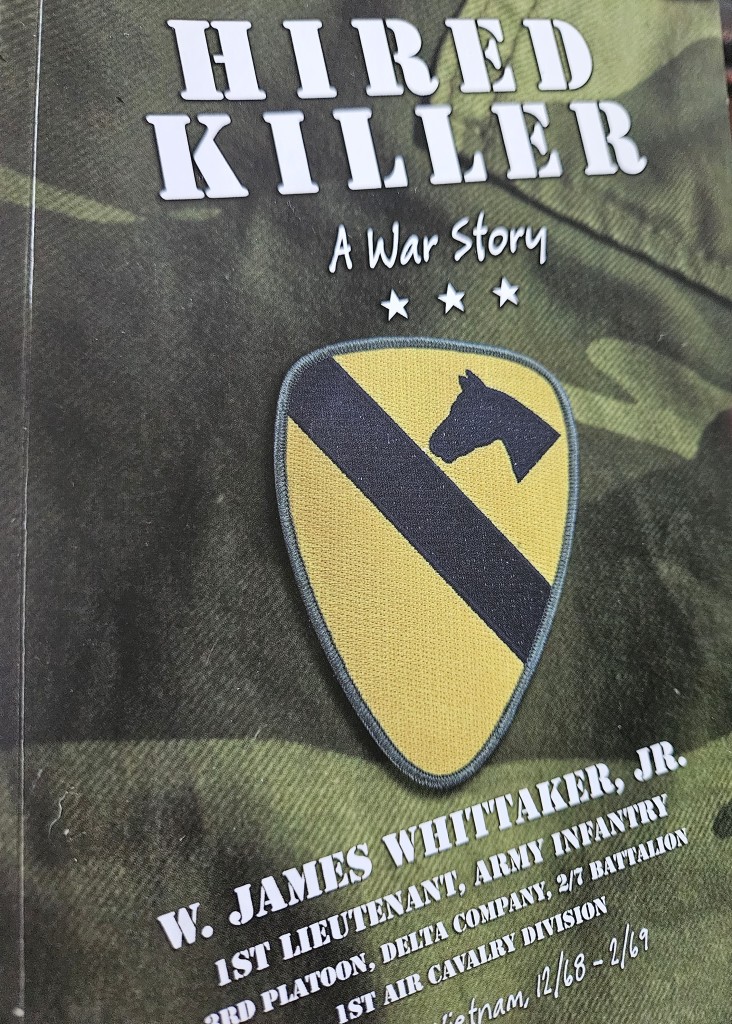

W. James Whittaker, Jr.’s Vietnam War memoir, Hired Killer: A War Story (Bookbaby, 96 pp., $20, paper) contains some intriguing chapter titles: “Into the Heart of Darkness,” “Finding Kurtz,” and “The Little White Pill.”

The book begins in late 1967 when, as a young man with a college degree and an Army commission as a 2nd Lieutenant, Jim Whittaker was assigned to the Infantry. “It was the peak of the war,” Whittaker writes. “Books have been written and classes taught about that pivotal [time] in American history. Some of the events nearly brought our country to its knees. It was, however, the never-ending war in Vietnam that tore us apart more than anything else.”

Whittabker arrived in-country at Cam Ranh Bay, then flew to An Khê, where he was issued a Colt .45 semiautomatic sidearm and an M-16. His next stop was Quản Lợi Base Camp where the young LT felt as though he had gone “out into the bush.”

Sometimes known as “Rocket City,” Quản Lợi, not far from the Cambodian border, was the headquarters of the 3rd Brigade of the 1st Air Cavalry Division. At one point, the “swirling clouds of red dust” being kicked up by helicopters landing and taking off, Whittaker says, created “a surreal feeling that I had been transported to an alien planet.” His reaction was: “What had I gotten myself into?”

Later, on a helicopter approaching LZ Sue, Whittaker found himself wishing he’d joined the Navy when he was put in charge of a platoon that would vary in size from 22-35 men, 80 percent of them draftees. It didn’t take him long to discover he just might not be taking part in a “good war” like the one in which his father fought. He soon began outwardly questioning military authority.

Jim Whittaker does the best job I’ve read of seamlessly explaining the meanings of Vietnam War military terms he uses throughout the book. He also tells his story well in a short, compact fashion, while finding a way to pack in a ton of information.

He shows great discipline in keeping the story to a small number of pages. That may actually encourage more people to read it. I hope so, because Hired Killer deserves to be read.

For ordering info, email jimwhit3@yahoo.com

–Bill McCloud