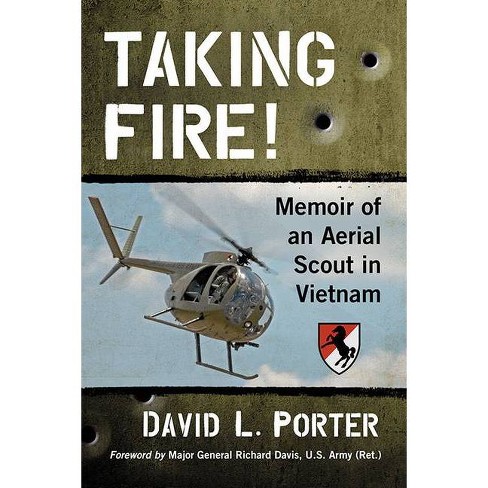

David L. Porter served twenty-seven years in the U.S. Army, retiring as as a colonel in 1995. The most memorable time of his career occurred when, immediately after he received his wings as a helicopter pilot, he flew the Hughes Cayuse OH-6 Scout LOH as an Aerial Scout Section Leader with the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment (known as the Thunderhorse) from Quan Loi, Vietnam in 1969-70.

Porter recalls those days in Taking Fire!: Memoir of an Aerial Scout in Vietnam (McFarland, 182 pp. $29.95, paper; $9.99, Kindle). Porter tells his story with “no surnames” and “no attempt to identify any themes nor to draw any conclusions.” He leaves those tasks to readers, he says, and claims to offer only his “description of events.”

The memoir revolves around Hunter-Killer operations, which died with the war. The tactic could not have been simpler: An OH-6 LOH (Light Observation Helicopter or “Loach”) flew around Viet Cong- and NVA-controlled territory at or below treetop level until it drew fire, then marked the spot with a smoke grenade. Instantly, an AH-1G Cobra waiting overhead would attack the area.

These encounters quickly escalated as Cobra pilots directed artillery onto enemy positions. Ideally, an Air Force OV-10 Bronco forward air controller then brought in F-4 Phantoms to finish the job.

American ground forces requested these missions, which were known as VR (visual reconnaissance) to try to find the elusive enemy. The ballsiest part of the operation fell to the LOH pilot—Porter’s role. An observer—called OSCAR—accompanied him and provided the primary set of eyes for locating the enemy. LOH pilots and OSCARs refused to consider themselves as bait.

Porter flew Thunderhorse Hunter-Killer strikes from October 1969 through February 1970. His recollection of facts during that time is astounding. The details of his physical and mental states often made me feel as if I were in his body or mind.

He brings everything to life, on the ground and in the air, on-duty and off. Although Porter uses no surnames, he gives us memorable personalities and dissects the idiosyncrasies of men of all ranks. For him as a lieutenant, watching and listening to experienced people was akin to attending school.

He examines LOH tactics in depth by analyzing missions and after-action discussions about arbitrary maneuvers such as which way to break over a target. His reflections on the morality of machine-gunning three VC—men he had initially attempted to capture—puts a heartrending slant on death, even in combat.

One might read Taking Fire! as a coming-of-age story. Frequent turnovers in commanders allowed Porter to analyze leadership techniques from aggressive and violent, to careful and deliberate and, I believe, establish his own criteria for how best to command troops. Furthermore, the losses and injuries of many close friends had a strong impact on Porter’s appreciation for life. That said, these conclusions are merely mine.

Without intending to do so, David Porter also convinced me (for at least my tenth time) that flying helicopters is the toughest aviation job in warfare.

—Henry Zeybel