Mon Cochran’s very readable memoir, Achilles Heel: A Vietnam Memoir (Eelman’s Press, 348 pp. $25, paper), written almost 60 years after the author’s service in the Vietnam War, is mainly focused on two cousins of privilege who grew up together and were best friends and best man at the other’s wedding.

Both joined the Marine Corps after college, and served in the Vietnam War, but at different times. One survived and the other did not. The survivor, the author, has spent a part of the rest of his life trying to come to terms with this fact, with survivor’s guilt and with PTSD.

Cochran, a life member of Vietnam Veterans of America, and his cousin, Bing Emerson, are of distinguished Massachusetts colonial lineage. The author’s mother was a Cabot, one of Boston’s old-line families. Emerson was a direct descendant of the famed philosopher and abolitionist Ralph Waldo Emerson. The cousins attended elite private schools and Harvard College, Class of 1964. (Full disclosure: I was in the same Harvard class, but never met them at Harvard or thereafter.)

Only about a third of the book covers the Vietnam War, but Cochran’s wartime experiences permeate the entire memoir. permeates the entire memoir. After two summers of the Platoon Leaders Course and six months of Quantico training, Cochran was assigned to Marine intelligence and expected to spend his remaining time in the service in Southern California with his wife.

However, the Vietnam War intervened and his unit, Marine Aircraft Group 36, was sent to Vietnam in August 1965. Cochran was the only non-flyer officer in his helicopter unit. His 13 months in I Corps was comprised of taking command of a rifle company for nighttime defense, working as a landing zone coordinator for extractions, many of which were hot, and eventually doing intelligence work. He received several Air Medals.

After the war Cochran tell us, he shut down emotionally and became an antiwar activist. He

went on to a distinguished academic career, which he chronicles in detail, after earning a Ph.D. in psychology at the University of Michigan and became a professor of early child development at Cornell. Cochran was considered one of the world’s leading experts in his field and has written several studies and books on the subject.

The book’s defining moment comes when he has returned from Vietnam and meets his cousin, who had just completed Marine flight training, and asks him “Why are we fighting in Vietnam?” Cochra responds, “to stop the spread of communism.” That personally dishonest response haunts Cochran thereafter, particularly after Emerson’s helicopter is shot down in Vietnam and he is killed.

Cochran suffers guilt, hypervigilance, and war-related nightmares. His PTSD manifests

itself particularly in response to each subsequent American war. His remedies are alcohol abuse, annual fishing trips, infidelity, and therapy. Writing the memoir perhaps has ha had a cathartic effect.

In general, privileged Americans avoided serving in the Vietnam War. That, however, does not apply to the 192 members of the 1,200 student Harvard Class of 1964 who served in the military, including scores who went to Vietnam.

About 12 percent of draft-eligible males served in the military during the Vietnam War, compared to 16 percent of the author’s and his cousin’s Harvard class.

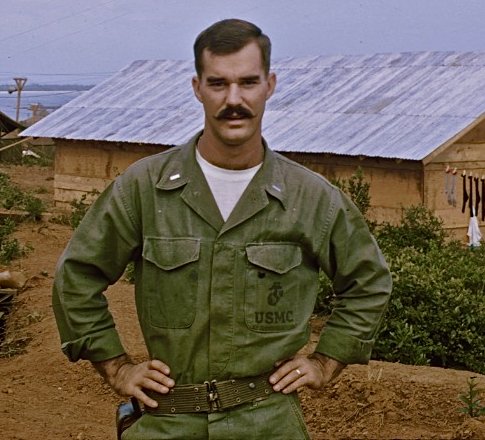

The books contains excellent photographs. However, there is no index or glossary. Nonetheless, I highly recommend Achilles Heel, which is almost as reminiscent of a Greek tragedy as it is of the Greek myth embodied in its title.

The author’s website is https://moncochran.com/

—Harvey Weiner