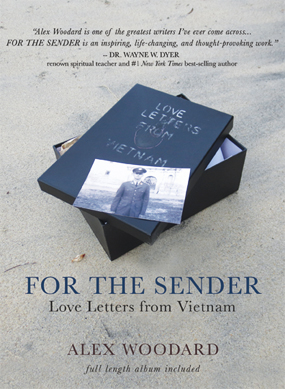

Author and singer/songwriter Alex Woodard has put together a most unusual book: For the Sender: Love Letters from Vietnam (Hay House, 233 pp., $19.99, hardcover; full-length CD of songs included). Woodard has taken a batch of real love letters written from an airman in Vietnam to his wife back home, and combined them with heartfelt imaginary letters his daughter could have written to her deceased father. Then, Woodard wrote songs based on these letters.

The airman, Sgt. John Fuller, apparently succumbed to the effects of PTSD after the war. He drank too much, was unfaithful to his wife, and never was at peace with himself. In 1998, John Fuller was shot to death by a locksmith who was changing the locks on Fuller’s girlfriend’s house after a domestic altercation. When Fuller charged him armed with a weapon, the locksmith defended himself. No charges were filed against the locksmith.

John Fuller’s daughter Jennifer, born in 1970, was devastated by the loss of her father. She retreated into a shell of anger and depression for several years. One winter day while helping her mother move, she came across a box of letters with “Love Letters from Vietnam” written on the lid. Overwhelmed—and not sure how to cope with this treasure chest of letters from her father—she contacted Alex Woodard. He agreed to put the letters to music, with lyrics adapted from her father’s words.

He also composed responses to letters written by Jennifer to her father as if Woodard were John Fuller himself stationed in Vietnam. Only a special kind of writer could undertake such a challenging endeavor and make his imaginary written responses sound believable.

Alex Woodard is not a veteran of any branch of service. However, he is a staunch advocate for veterans. He describes in detail several encounters he has had in recent years with veterans of the wars in Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan. He went surfing with one group who claimed it helped them cope with PTSD. He worked with another group learning to ride and care for horses as part of their recovery from PTSD and traumatic brain injury. He describes encountering a man who rescues dogs from kill shelters and trains them to be service dogs for veterans.

Alex Woodard

Much of the book is about Woodard’s own life experiences, such as the near loss of his mountain home to a forest fire and the subsequent flooding and mudslide. It is disconcerting at times when he inserts a letter from Sgt. Fuller or Jennifer Fuller into the middle of his story on a totally different topic.

However, the CD included with the book that features Woodard as Sergeant Fuller and his friend Molly Jensen as Jennifer more than makes up for the occasional distraction.

Trusting Alex Woodard to read letters from her father and then to write letters as if they were written by her father to her turned out to be a truly healing experience for Jennifer Fuller. It helped her find peace and forgiveness and move on with her life.

The author’s website is www.alexwoodard.com

—James Coan

A memoir normally has a purpose beyond simply recounting what the writer did over a given period of time. William S. Fee follows this pattern in Memoir of Vietnam 1967 (Little Miami, 122 pp. $15) by describing how military training and combat turned his infantry squad into a family.

A memoir normally has a purpose beyond simply recounting what the writer did over a given period of time. William S. Fee follows this pattern in Memoir of Vietnam 1967 (Little Miami, 122 pp. $15) by describing how military training and combat turned his infantry squad into a family.

Throughout his life Charles W. Newhall, III has engaged the world with ferocious intensity. The son of a World War II Army Air Corps colonel, Newhall was raised to uphold his family’s military tradition, which extends back to the Civil War. That guidance and his reading as a student at military schools instilled an ethos encompassed by warriors from all of history.

Throughout his life Charles W. Newhall, III has engaged the world with ferocious intensity. The son of a World War II Army Air Corps colonel, Newhall was raised to uphold his family’s military tradition, which extends back to the Civil War. That guidance and his reading as a student at military schools instilled an ethos encompassed by warriors from all of history.

Allan A. Lobeck’s Marshall’s Marauders (Lulu, 396 pp., $33.92; $2.99, Kindle) has one unique feature: Of the hundreds of Vietnam War novels I have read, this is the only one that has no page numbers. I found that very frustrating, especially as this is a very large book.

Allan A. Lobeck’s Marshall’s Marauders (Lulu, 396 pp., $33.92; $2.99, Kindle) has one unique feature: Of the hundreds of Vietnam War novels I have read, this is the only one that has no page numbers. I found that very frustrating, especially as this is a very large book.

Gus Willemin

Gus Willemin

Kinsler never exactly spells out details about where he served in Vietnam or his unit. But , along the way he does mention Pleiku and the 4th Infantry Division. He also talks about Hill 684, Kontum, and spending much time in the northern part of II Corps near Cambodia.

Kinsler never exactly spells out details about where he served in Vietnam or his unit. But , along the way he does mention Pleiku and the 4th Infantry Division. He also talks about Hill 684, Kontum, and spending much time in the northern part of II Corps near Cambodia. The resigned stare on the face that fills the back cover of The Other Side of Me: Memoirs of a Vietnam Marine (CreateSpace, 169 pp., $12.25, paper) pretty much tells the book’s entire story. The stare belonged to ammunition technician D.L. “Tex” Swafford, who served three tours in Vietnam, from 1966-70, and who died last year. Swafford called the book “my story in random narrative and prose, essays, awkward and sometimes dark poetry, thoughts and words of a man with a broken mind.”

The resigned stare on the face that fills the back cover of The Other Side of Me: Memoirs of a Vietnam Marine (CreateSpace, 169 pp., $12.25, paper) pretty much tells the book’s entire story. The stare belonged to ammunition technician D.L. “Tex” Swafford, who served three tours in Vietnam, from 1966-70, and who died last year. Swafford called the book “my story in random narrative and prose, essays, awkward and sometimes dark poetry, thoughts and words of a man with a broken mind.” Donald Swafford

Donald Swafford